Every ambitious SaaS founder and CTO eventually discovers a painful truth: great ideas and fast early traction are not enough. The bottleneck often comes not from product-market fit, but from the architectural foundation. Software that felt nimble with 1,000 users can start to buckle when 10,000 arrive. Teams that once shipped weekly releases suddenly find themselves tangled in dependencies, slowed down by integration nightmares, and frustrated by outages caused by seemingly unrelated changes. This is when many consider microservices architecture as their solution.

This is the point where many turn to microservices architecture, a model that promises independent scaling, resilience against failure, and alignment between technical boundaries and business capabilities. On paper, it’s the perfect answer to growth pains. In reality, it’s much more complicated. Microservices architecture solves some problems brilliantly while creating others that can be equally crippling if implemented too early or without proper foundations.

The real question isn’t whether microservices architecture is trendy or elegant—it’s whether it solves the right problems at the right stage of growth. This article offers a framework for CTOs and founders to make that decision deliberately. It explores the strengths and limits of monoliths, the realities of microservices architecture, the organizational and technical maturity required, and the practical steps to migrate when the time is right. Above all, it reframes microservices architecture not as a buzzword but as a strategic business decision that carries costs as well as opportunities.

Monoliths: The Natural Starting Point

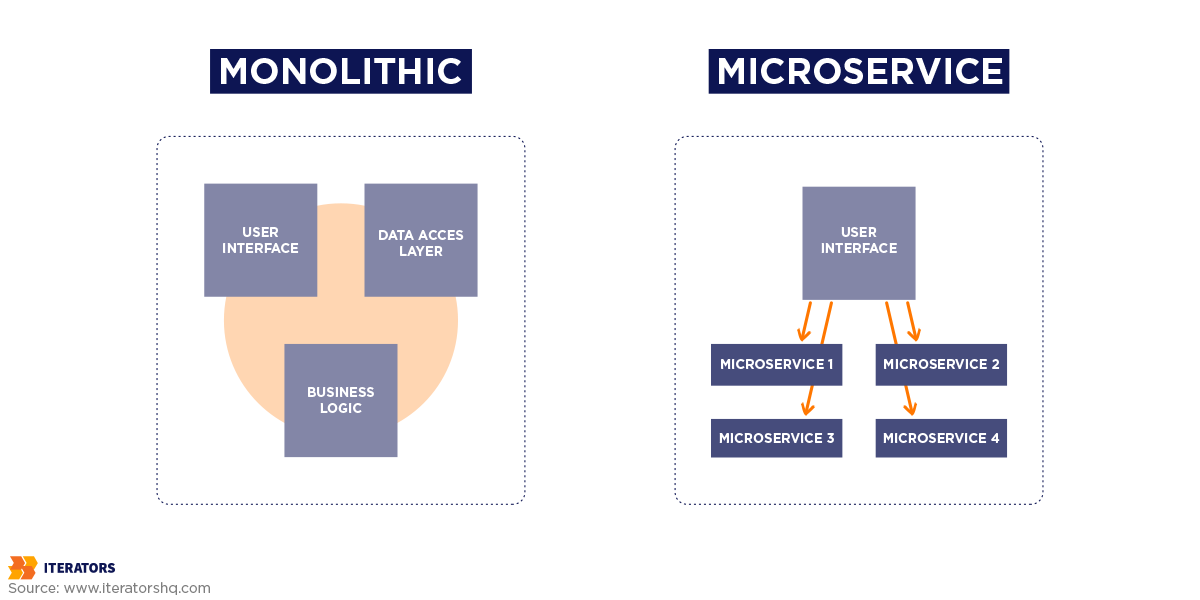

Every SaaS platform begins, intentionally or not, with a monolith. A monolithic application bundles all business logic into a single, unified codebase. For small teams, this structure is not a weakness but a strength. One repository, one deployment pipeline, one database—everything is together, fast to change, and easy to understand.

Most successful SaaS companies you admire today started this way. Shopify was monolithic for years. Slack, before its global growth, relied on a simple structure. The advantages are obvious: faster iteration cycles, lower infrastructure costs, and minimal communication overhead between engineers. For startups in the discovery phase, the monolith is often the only sensible choice.

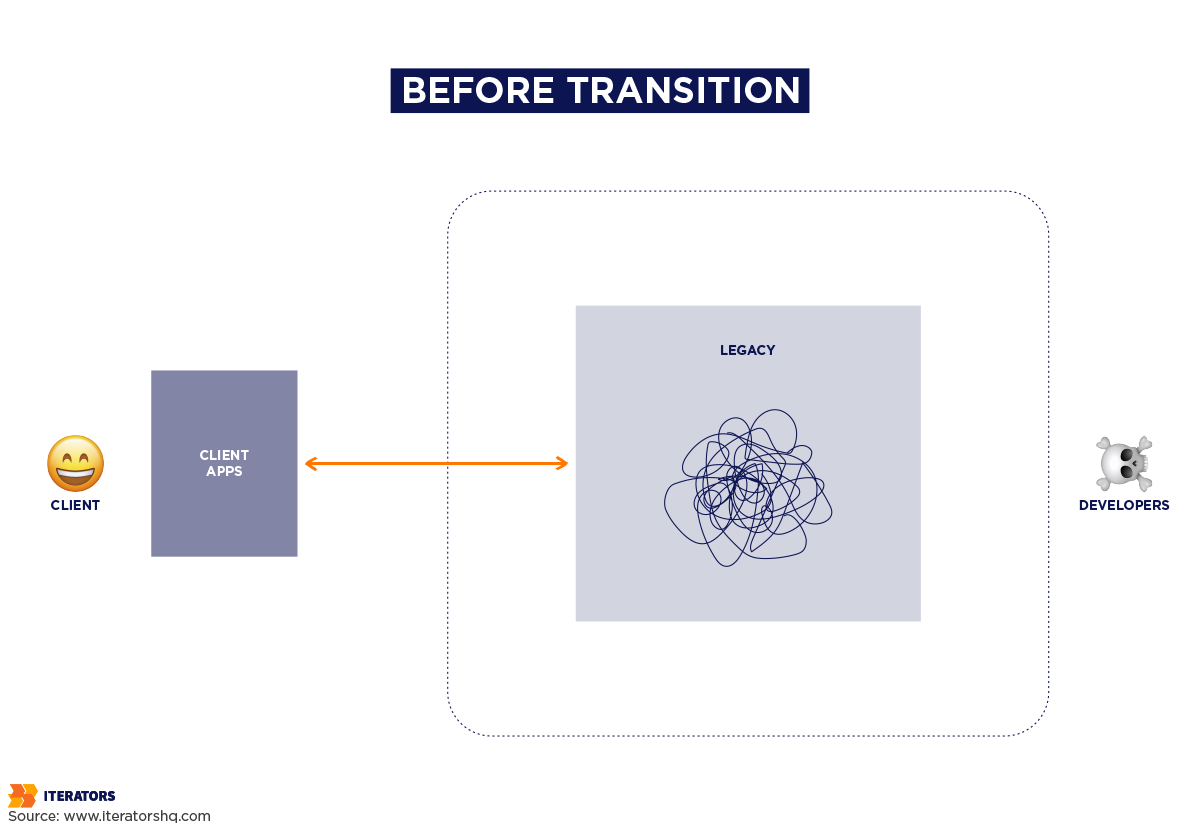

But scaling introduces strain. A reporting feature under heavy load forces the entire system to scale. Deployment pipelines slow down when every new feature requires redeploying the entire codebase. A bug in one small module can bring down unrelated services. And as the team grows from five to twenty engineers, merge conflicts, unclear ownership, and clashing priorities start to paralyze productivity.

The monolith isn’t “bad”—it’s just limited. It’s excellent for product-market fit, but poor at supporting sustained growth. The challenge for leaders is to recognize the signs that those limits are approaching.

When the Monolith Starts to Hurt: Signals to Watch

The temptation to abandon a monolith too early is strong, but often wrong. The smarter move is to identify clear signals that justify moving to microservices architecture:

Your release cycles are slowing not because of bad processes but because the monolith’s coupling forces every team to coordinate.

Scaling costs are rising too much because you must provision for the “hottest” module by scaling the entire system.

Enterprise integrations or custom features threaten to bloat the codebase with client-specific hacks.

Team boundaries no longer map cleanly to code boundaries, leading to constant stepping on each other’s work.

These pain points signal that the monolith is not only slowing growth but actively hurting team morale and customer trust. They form the business justification for exploring microservices architecture.

The Microservices Architecture Promise—and the Catch

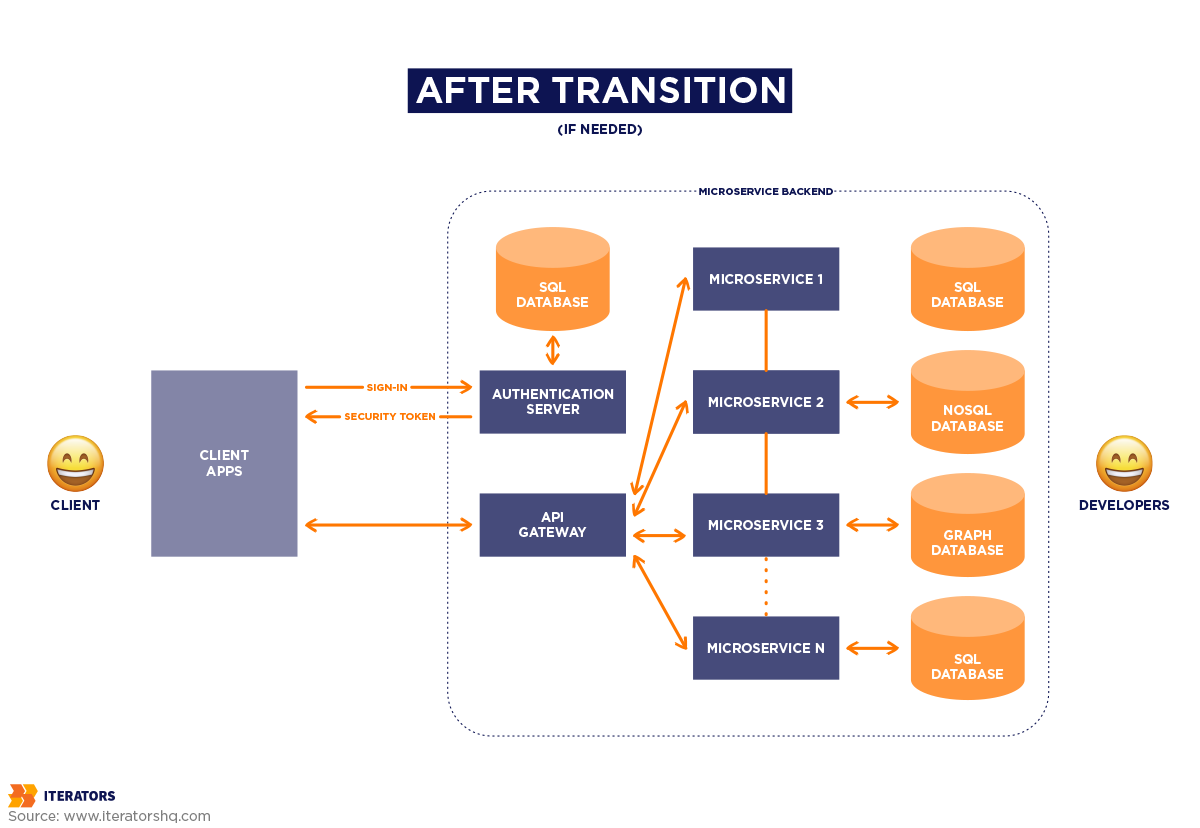

Microservices architecture, in its ideal form, breaks down the system into autonomous services, each with its own codebase, database, and release pipeline. It allows scaling only the services under pressure. It localizes failures so that a bug in billing doesn’t crash authentication. It lets teams own specific services end to end, avoiding the coordination nightmare of a shared monolith.

Netflix is the classic poster child, scaling to millions of concurrent streams with high availability. But Netflix had hundreds of engineers and a decade of operational investment when it made the transition. For mid-stage SaaS, the story is more complex.

Adopting microservices architecture requires not only technical re-architecture but organizational transformation. Teams must become smaller, more autonomous, and accountable for operating what they build. Observability, automation, and incident response become table stakes. Without these foundations, companies end up with a “distributed monolith”—a brittle web of services tightly coupled by shared databases or synchronous dependencies.

A Decision Framework for Microservices Architecture

So how does a CTO decide whether microservices architecture is the right path? The best lens is not ideology but readiness. Below is a checklist against which SaaS leaders can measure their situation.

Business Capability Separation – Do you have clear, stable domains (authentication, billing, analytics) that map naturally to services? If your business model is still in flux, don’t fragment too early.

Release Train Pressure – Are teams blocked because they can’t release independently? If separate groups need to ship at different speeds, microservices architecture may provide relief.

Scaling Needs – Is one part of the system consuming most infrastructure resources? If yes, independent scaling could yield efficiency.

Operational Maturity – Do you already have CI/CD pipelines, automated testing, monitoring, and on-call practices? Without these, microservices architecture multiplies chaos.

Team Structure – Are teams cross-functional and small enough to own services end-to-end? Conway’s Law ensures architecture mirrors organization.

Budget & Headcount – Can you afford the 15–25% engineering overhead microservices architecture initially imposes for infrastructure, observability, and operations?

If most of these conditions are unmet, you are not ready. The smarter move is to evolve your monolith into a modular monolith—a monolith with clear internal boundaries—until the business case demands more.

Modular Monolith: The Often-Ignored Middle Path

Between the extremes of “pure monolith” and “microservices architecture everywhere” lies a practical compromise: the modular monolith. In this model, the codebase remains unified, but modules are structured with strict boundaries. This allows teams to decouple logic internally, prepare for eventual decomposition, and still enjoy the simplicity of a single deployment.

A modular monolith should not be seen as a failure to embrace microservices architecture but as a deliberate staging ground. It allows leaders to defer complexity until it’s justified while still gaining some benefits of separation.

Migration Blueprint: From Monolith to Microservices Architecture

Assuming the business case is strong, how should SaaS companies migrate? The most reliable approach is the Strangler Fig Pattern—gradually replacing parts of the monolith with services. Here’s a structured but realistic blueprint:

Phase 1: Assessment (Weeks 1–3)

Map your current architecture, identify hot spots (modules under scaling stress), and define clear service boundaries. Establish metrics: deployment frequency, mean time to recovery, and error rates.

Phase 2: Foundation (Weeks 4–6)

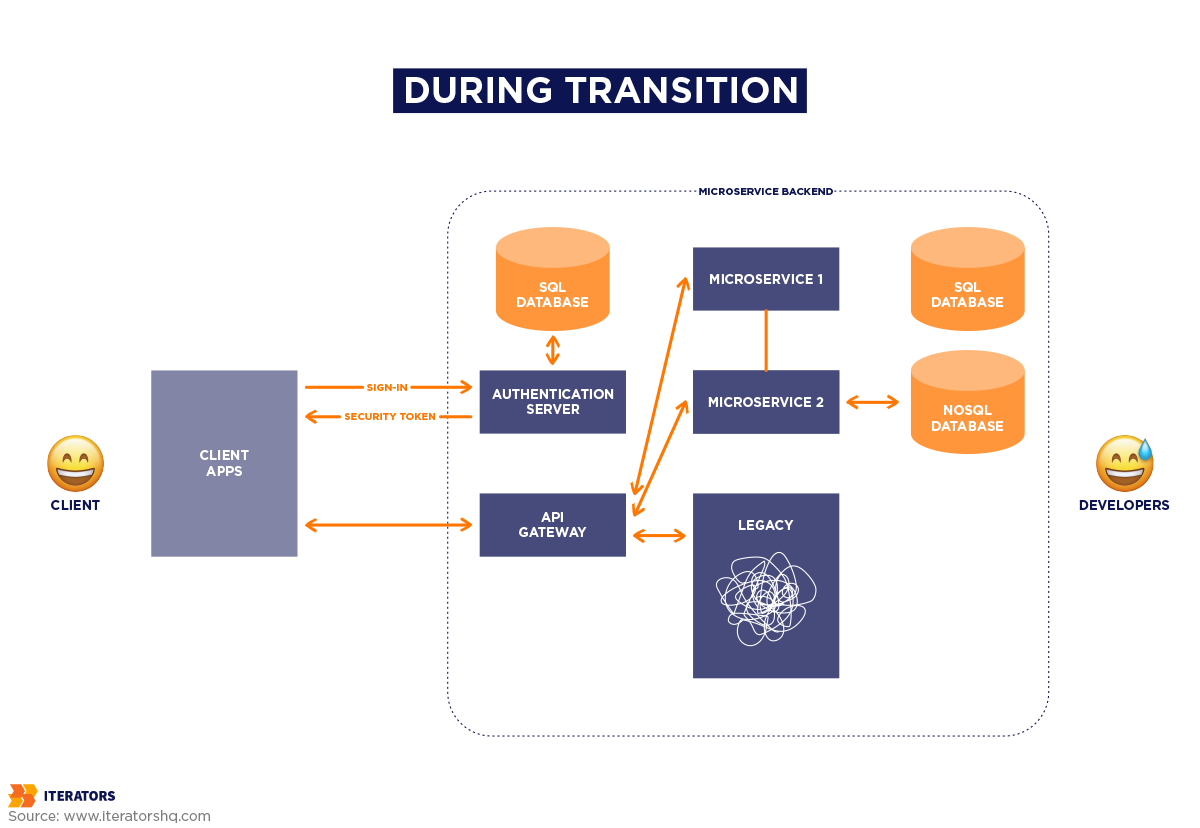

Invest in the platform first: CI/CD pipelines, monitoring, tracing, an API gateway, and a messaging broker. Define standards for APIs, error handling, and observability before extracting services.

Phase 3: First Extraction (Weeks 7–10)

Choose a low-risk, high-value module (e.g., notifications or reporting). Build it as an independent service with its own database. Route traffic via the gateway. Keep fallbacks in place.

Phase 4: Cutover & Validation (Weeks 11–12)

Deploy the service, run shadow traffic, and validate against metrics. Test observability, incident response, and rollback procedures. Only then consider extracting the next service.

Phase 5: Iteration & Scaling (Ongoing)

Repeat for other modules, starting with those most constrained by the monolith. Regularly review whether the complexity is delivering measurable business benefits.

The Hardest Challenge: Data Consistency in Microservices Architecture

Perhaps the single most underestimated challenge in microservices architecture is data. In a monolith, transactions ensure atomicity. In microservices architecture, each service owns its own database, making cross-service consistency difficult.

The solution is to embrace eventual consistency. For example, when a user upgrades their subscription, the billing service records the payment, then publishes an event. The analytics service and notification service subscribe and update their states asynchronously. This means different parts of the system may be briefly inconsistent, but they will converge.

Patterns like sagas (coordinated multi-step workflows with compensating actions) and event sourcing (storing every state-changing event for replay) are vital here. The outbox pattern—where changes are written to both a database and an event log in a single transaction—ensures events are never lost.

For compliance-heavy SaaS, especially in fintech or healthcare, these patterns are not optional—they are survival requirements.

Operational Reality: Tooling and Overhead

Running microservices architecture is not simply a matter of design; it is an operational lifestyle. Each service requires deployment pipelines, monitoring, scaling policies, and incident handling. Without automation, the overhead will crush teams.

Containerization with Docker is the baseline. Kubernetes often becomes inevitable at scale, though its complexity can be daunting. Managed services like AWS ECS or Google Cloud Run provide a gentler path. A service mesh (Istio, Linkerd) adds resilience with service discovery, routing, and encryption. API gateways unify client entry points and enforce authentication, throttling, and routing policies.

Most importantly, observability becomes a non-negotiable pillar. A single user request may traverse six services; without distributed tracing and centralized logging, debugging becomes impossible. Tools like Prometheus, Grafana, and Jaeger—or commercial platforms like Datadog—are the lifeline of operational sanity.

Organizational Alignment: Microservices Architecture Mirrors Teams

Microservices architecture is as much an organizational change as a technical one. A service owned by no one is a service that fails. Amazon’s “two-pizza rule”—teams small enough to be fed by two pizzas—captures the principle but not the detail.

A real microservices architecture organization requires cross-functional teams. A payments team must include backend developers, frontend engineers, DevOps, and domain experts. They must be capable of building, deploying, and supporting their service independently. Anything less recreates the bottlenecks of a monolith in distributed form.

APIs must be treated as contracts, versioned carefully, and backward-compatible. Teams need shared standards for testing, deployment, and monitoring. Without these, the system devolves into chaos.

Measuring Success: Technical and Business Metrics

The measure of success is not how many services you run but whether they create business value.

On the technical side, track:

- Deployment frequency

- Lead time for changes

- Mean time to recovery

- Service availability

On the business side, measure:

- Are features shipping faster?

- Are enterprise clients satisfied with integration flexibility?

- Are scaling costs under control?

If the answers are negative, microservices architecture is not solving the real problems.

Case Insights: Lessons from the Field

At Iterators, we’ve seen both sides of this journey.

For Virbe, a conversational commerce platform, we built a microservices architecture system on AWS. The separation allowed fast iteration on customer-facing features while scaling back-end analytics independently. The key lesson: contract testing between services prevented drift and reduced incidents during deployments.

For KLIX, operating across multiple countries, tenant isolation was paramount. A schema-per-region model, combined with read models for reporting, stabilized analytics latency while avoiding cross-database joins. The lesson: data partitioning is as critical as service partitioning.

These stories highlight that microservices architecture succeeds not because of abstract design patterns but because architecture directly addressed real business pressures.

The Future of SaaS Architecture

Microservices architecture is not the endpoint. Emerging paradigms continue to reshape SaaS.

Serverless computing pushes modularity further, letting individual functions scale independently. SaaS platforms with spiky or seasonal workloads benefit enormously.

AI-powered ops are making microservices architecture more accessible, offering predictive scaling, anomaly detection, and automated remediation.

Edge computing allows SaaS providers to deploy services closer to users, reducing latency and improving reliability in global markets.

But the principle remains the same: architecture must serve the business, not the other way around.

Conclusion: Architecture as a Strategic Business Decision

Microservices architecture is not a silver bullet, nor is it a mere technical trend. It is a strategic decision that can accelerate growth—or derail it.

For most SaaS startups, a well-structured monolith or modular monolith is the right foundation. Microservices architecture should only be adopted when scaling pressures, enterprise demands, or organizational growth justify the overhead. When it is adopted, success comes not from technical wizardry but from deliberate organizational alignment, operational discipline, and clear-eyed evaluation of trade-offs.

The path is best taken gradually: build a modular monolith, invest in automation and observability, and then decompose deliberately using proven migration patterns. Done well, microservices architecture allows SaaS companies to scale efficiently, deliver features rapidly, and meet the demands of enterprise clients. Done poorly, it creates fragmentation, overhead, and fragility.

The choice, ultimately, is not whether microservices architecture is fashionable but whether it aligns with your company’s readiness and strategic goals. For CTOs and founders, that is the architectural decision that defines not just the system, but the business itself.

If you’re navigating these architectural decisions for your SaaS company, you don’t have to make them alone. At Iterators, we specialize in helping startups and scale-ups make the right technical choices at the right time. Schedule a free consultation to discuss your specific scaling challenges and architectural strategy.